Solidarity in the Carpathian Region

Sándor Köles is a Hungarian-born sociologist, the President of the Carpathian Foundation, a founding member of the PASS Board of Advisors, and a member of the Berlin-based Robert Bosch Academy. He had been the Senior Vice-President of the International Center for Democratic Transition (ICDT), the main goal was to share and make applicable Central European experiences on democratic transition in a wider world. Previously, he had been the Carpathian Foundation’s Executive Director, promoting cross-border and interethnic cooperation in the bordering areas of Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Ukraine. He is the author and editor of books, articles, studies, and documentaries on civil society, regional and cross-border cooperation, and ethnic minorities.

This article was written by Sándor Köles. It is translated from Hungarian.

Solidarity

Solidarity is a very timely topic today. The Syrian refugee crisis of 2015 has dramatically confronted us with the way in which a universal ethical norm, solidarity, is violated on the global stage by short-sighted political profiteering and the selfish and convenient indifference of wealthy states to those fleeing war and climate change. In doing so, it manipulatively overrides the ethos of solidarity to make it the norm, which in the long run erodes the cohesive, integrative force that solidarity in the narrow and broad sense represents. We also see that while there is more and more talk about a Europe of solidarity, it is precisely the member-state conflicts (quota disputes, etc.) between Western and Central-Eastern Europe caused by the refugee crisis that indicate that European governments are confronting their own declared core values, including the idea and practice of European solidarity. All this shows how fragile and how easily the threads of solidarity can be broken, and how this conflict has resurfaced Europe’s traditional divisions between its Western and Eastern halves, and the outlines of new geopolitical blocs have emerged on the European horizon, which political demagoguery falsely tries to reduce to a struggle between ‘pro-immigration’ and ‘anti-immigration’ countries. But we can also see how the Russian-Ukrainian war has united the Western hemisphere and strengthened European solidarity with Ukraine, highlighting the importance of neighborhood and common cultural space in the development of solidarity.

The experience of solidarity is as old as humanity itself, with roots going further back than those of any political system or power structure. It stems from the recognition of individuals’ mutual interdependence and has enabled the survival of groups as functioning as communities. There were rational reasons for this solidarity, but at the same time, it was also an emotional bond shared by community members. Christianity had brought solidarity to the forefront of human relations, and a defining ethical requirement (brotherly love, aiding the needy, etc.) and it had also been the root of philanthropic ideas. Solidarity gained political citizenship via the French Revolution’s tripartite slogan and has gone on to become a fundamental premise for social progress and modern democracy. In a mutually requisite trinity of liberty, equality, and fraternity, it is fraternity that is interpretable as solidarity, and which eases the tension between liberty and equality. Without liberty, there is no equality, and without fraternity – that is solidarity – there can be no liberty, and therefore no equality.

On a primary level, solidarity is an emotional relation eliciting elemental empathy toward those facing hardship, such as natural disasters, illness, or poverty. What marks this emotion as something other than pity is that compassion is mutual. Not only do I empathize with another’s situation, I can also count on others being compassionate toward me, and this fosters mutual trust. Solidarity is a safety net of trust than prevents individuals from falling away from the community, and the thicker this weave of trust and solidarity, the better the net holds. Reinforced with empathy and mutual trust, emotional ties are taken to the next level, that of conscious mutual dependence. It is this conscious aspect that elevates compassion to active solidarity. Solidarity, at a primary level, is an emotional relationship that evokes an elementary compassion for those in difficulty – be they victims of natural disasters, sick children or the fallen – but what distinguishes this compassion from pity is that it is reciprocal. Not only do I empathize with the other person and experience their situation, but I can count on the other person to empathize with me; they experience my situation and therefore I can trust them, just as they can trust me. Solidarity is a community web of trust that protects the individual from falling out of the community, and the more tightly woven this web of trust and solidarity is, the more it will hold. And if solidarity is based on empathy and this mutual trust, then the emotional relationship is replaced by a higher degree of solidarity: an awareness of interdependence – and this awareness turn compassion into solidarity in action.

The existence of solidarity is not felt because it is a natural part of everyday normality; its absence becomes conspicuous when this invisible bond is weakened, the fabric of society unravels and the cohesiveness of communities is broken. It is no accident that autocratic regimes begin their rule by demolishing the institutions of solidarity, nor was it incidental that during the democratic turn in Poland, dissident forces rallied around the banner of solidarity. Dismantling solidarity is a gradual process, and difficult to notice because of its greatly delayed symptoms, which cause devastating damage. To paraphrase Ralf Dahrendorf’s bon mot, while a system of government can be reformed in six months, a system of the economy takes six years, while social change requires sixty years – we may say that while undoing the bonds of solidarity takes a great deal of time, so does their repair is much more time.

With Europe being rebuilt on the ruins of World War II, conclusions were drawn from the two catastrophic wars to voice a new axiom, whereby conflicts between nation states should be transformed into cooperation, which requires mutual trust and most essentially, solidarity that expresses the interdependence and desire for peace of European nations. Going to war against one another was found to be a devastating way of resolving conflicts. As one of the “founding fathers” of Europe Jean Monnet had said in the 50s, “Rather than head-on conflict, they allow themselves to be mutually influenced. It is with help from the other that they may discover what they had been unaware of, so that dialogue and joint action shall be a matter of course.”

The Carpathian Euroregion

In this process of multi-level European reconstruction, the first Euroregions, established in the 1950s and 1960s, played a less visible but all the more important role in confidence building, dialogue, cooperation, and solidarity at the border regions, and thus as both became the precursors and promoters of European integration. Solidarity in cross-border cooperation is not an abstract model, but a very tangible space in a well-defined socio-ecological-cultural space, in which cooperative interactions to solve a common problem weave almost imperceptibly the threads of solidarity between communities and individuals in a region, which may have been at odds with each other in the past, creating a regional identity and associated patterns of solidarity alongside local, national identity.

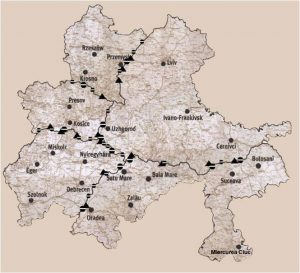

The territory of the Carpathian Euroregion, which overlaps the Carpathian Mountain range, is 161,000 sq. km and its population is close to 16 million. Its main goal is to generate and promote cross-border cooperation between local municipalities and institutions. In 1995 the Carpathian Foundation was established aiming to support grassroots cross-border initiatives and strengthen the resilience of local communities.

Both institutions of the Carpathians were conceived in the spirit of the desirable Central European vision of neighboring nations, which have been at enmity with each other for centuries and often changing statehood, redefining their relationship with each other, and moving toward mutually beneficial cooperation, respecting existing differences and for the benefit of each other. The democratic turnaround of 1989 offered a rare historical opportunity in the history of Central Europe for these nations to break out of the vicious circle of anti-democratic ethnonationalism, where easily fomented national sentiments served to ‘compensate’ for the social injustices, lack of freedom, and authoritarianism of the ruling powers that had arisen as a result of the anti-democratic traditions of these societies. The changes in Central Europe also provided an opportunity for these countries to attempt, now within a European and democratic framework, to go beyond the ‘misery of the small states of Eastern Europe’ and to cooperate in Central Europe.

As state borders do not coincide with ethnic borders and a significant number of national minority groups live separated from the “mother country”, the Carpathian region is the most ethnically divided region of Europe. This is conducive to the fomenting of ethnic-based national animosities, resulting in the reinforcement of persistent mistrust and mutual prejudice. In this framework, solidarity is unilaterally linked to national identity and exclusively to one’s own nationality (‘kindred’, ‘own race’) and stands in sharp contrast to the identity and solidarity of another nation. This ethnic solidarity, anchored in a ‘state religion’, has precluded the possibility of solidarity across ethnicities and borders, for example between oppressed classes in similar situations. In this closed ethnic solidarity, it is necessary to find and name the common enemy against which one’s own national identity and cohesion can be strengthened. In this closed solidarity, “your hero is our enemy”; and in which the same event is a national celebration for one, a national tragedy for another. Is it possible to change this entrenchment, which is moving along a historical trajectory of necessity? Can there be a common memory in which “your heroes” can peacefully coexist with “our heroes” and in which there is a mutual willingness to understand each other’s national tragedy and national day?

The Carpathian Euroregion is ostensibly an imprint of Central Europe, but beneath the surface, it is a dense agglomeration of national minorities and diverse ethnocultural groups, with a wide range of cultures congested in a relatively small area. This region, with its specific natural characteristics as the Carpathian Mountains and its ethnic, cultural, and landscape diversity, is a Central European microcosm under the accumulating rubble of history. This microcosm is not simply a random set of border regions of the five countries concerned, but a different quality; a cultural space shaped by the interactions between the ethnic and ethnocultural groups that live here and culminating in a specific common mentality, which we might call “Homo Carpaticus”, which is the basis of a common regional identity, situated hiddenly between local and national identities.

Solidarity in the Region

In this microcosm, the threads of solidarity are stronger than in the larger, Central European space, because the preconditions of solidarity, such as similarity of situation, common destiny and interdependence, are given in both physical and spiritual terms, and therefore the solidarity of the Carpathians transcends national and ethnic determinations. This unique character and tradition has several distinct but closely interrelated layers: the Carpathian Mountain themselves, with their specific way of life, the region’s perennial peripheral location, its often changing statehood have changed seven times in the last hundred years) and the cultural pattern shaped by the inevitable density of inter-ethnic interactions.

In the sparsely populated and inaccessible mountain ranges of the Carpathians, there were no contact surfaces between the indigenous ethnocultural groups such as the Hutsuls, Lemkos, Gorals, Mocs, Ruthenians, etc., due to their isolation, and therefore no unified Carpathian mountain identity could develop, but strong solidarity was formed in the local communities due to the mountain way of life. The fact that these areas were sheltered far from the centers also made them closed and distrustful of outside interventions and reticent to innovations. Hence, in part, the inherent conservatism of ‘Homo Carpaticus’. The closed mountain region was linked by a natural division of labor and exchange of goods to the more open valley towns, which became multi-ethnic through immigration and settlement and were the centers of this exchange. In this barter, reciprocity was expressed, since the exchange gave them access to products like wood or wheat that neither of them had separately. This exchange of goods was also an exchange of culture and information which enabled people with different ethnic backgrounds to get to know each other. This mutual communication required knowledge of each other’s languages, which helped the towns of the Carpathian region to become multilingual and thus multicultural communities, in which ethnic identities were dissolved in the self-conscious identity of the local citizen, in which tolerance towards each other was the defining element of solidarity and which constitutes another layer of the Carpathian character and tradition.

The third layer of Carpathian tradition is tied to the great diversity of local and cultural autonomy present in the region, historically from the 12th-13th centuries well into the early 20th century. For brevity’s sake we shall refrain from listing and describing these in detail; let it suffice to mention Transylvanian self-sufficiency necessitated by history, including the Saxon, German Armenian, and Sicular autonomies that shaped the region’s unique character. A similar, yet different territorial autonomy is that of Galicia which included the Eastern Carpathian mountains and was an autonomous part of the Habsburg Empire; or the limited autonomy of multiethnic Bucovina in the Southern Carpathians, on what is today the Ukrainian-Romanian border. But we could mention the Saxon (“Zipsers”) flourishing in the 13th century in the Szepes/Spys region of the Northern Carpathians, on today’s Slovakian-Polish border, which for centuries had regional municipalities similar to the Cantons of Switzerland. All this was formative of the Carpathian image, through architectural and cultural heritage as well as self-governance practices and multicultural traditions. These micro-regional autonomies are now all but gone, along with the braces of solidarity holding them together; but still, they retain a presence in collective memory.

Another defining layer of the Carpathian region’s unique character is the relationship of the changing state formations that share the Carpathians with the region. These state formations have always considered the region as a periphery. Northeastern Hungary is a periphery of Hungary; eastern Slovakia is a periphery of Czechoslovakia and later Slovakia; northwestern Romania is a periphery of Romania; southeastern Poland is a periphery of Poland and western Ukraine is a periphery of Ukraine. Peripheral because the Carpathian region is difficult to homogenize and the territorial or even cultural autonomy that characterized the Carpathians is incompatible with centralized nation-state concepts.

In the past century alone, borders had shifted six times, bringing with them the historical necessity of adapting to a different statehood, majority culture, and language. These changes had been tolerated by Homo Carpathicus passively, with a historically grounded and self-defensive philosophy of “nil admirari” (or “marvel at nothing”), though in a non-Horatian spirit.

Solidarity is alive and strong in the Carpathians, as evidenced by the attitude of local communities towards the millions of Ukrainians fleeing Russian aggression against Ukraine through the Carpathian Mountains along Ukraine’s western borders with Hungary, Poland, and Romania. They meet here with expressions of solidarity from hundreds of local communities in the Carpathians who did not wait for their central governments’ measures but acted spontaneously and self-organizing way since the very beginning of the war. For the “Homo Carpaticus” the refugees are not a faceless mass. Each of them has its own sad or even tragic story, and the local people in the Carpathians understand this because they experienced the same situation in the past.

The solidarity with the Ukrainian refugees could give momentum for the Carpathians to renew their institutions, the Carpathian Euroregion and the Carpathian Foundation, and explore and adapt Carpathian traditions for the future.

What traditions and new instruments could be carried over into the 21st century?

- Local communities need an immune boost to resist the persistent ethno-nationalist agitation imposed on them from outside and above, as well as national isolation. It begins with initiating small and ever-expanding circles of solidarity, in which civil societies may have a definitive role. These circles of solidarity must then be connected first on a regional, then an interregional level, to create societies a space for mutually supportive cooperation, to eventually plug the Carpathians into vital European circulation. A good instrument to this the Carpathian Civil Society Platform and Hub, which has been created by the Carpathian Foundation.

- Carpathian ecological and cultural heritage is a prominent European value, one which Europe knows little or nothing about. While the Alps can claim a vivid and differentiated image, the Carpathians are at best identified with Dracula. Formulating a Carpathian promotional strategy should be a priority, in order to authentically present the Carpathian “microcosm” and its image, shaped by interethnic and multicultural relations. This can contribute to strengthening regional identity.

- In light of Carpathian historical multilingualism, borderland schools’ curriculum should include not only a Western second language but an optional language of the bordering country. Multilingualism contributes to multilateral bonding, and understanding of others’ identities and cultures, with the added practical benefit of improving young people’s labor market position and prospective entrepreneurship opportunities within the Carpathians.

- For high schools in the Carpathian Euroregion, introducing a reader presenting regional history. There have been attempts at such a project but were ultimately unsuccessful at applying conventional history teaching clichés to the subject matter, modeling the Carpathians along five national histories. This led to fruitless debates on which tribe or nation was first, which populated and ruled the Carpathian Basin, or how specific historical events should be interpreted. Our proposed Carpathian Reader would focus on local (regional) everyday history; the formation of the landscape’s geography; how the barters worked; how local autonomies functioned in everyday life; mountain agriculture; interethnic relations; industrialization of the region, etc. Such a reader would make a major contribution to promoting Carpathian identity and mutual understanding, leading to a boost in regional solidarity.

Lots of effort is needed to climb the mountain!

Got something to say?