The Value of Peacekeeping

How has peacekeeping evolved in the last 70 years? Define its role in the 21st century.

The first peacekeeping mission was the armistice agreement on the Israeli border, but UN Peacekeeping has evolved quite a bit since then. Now, peacekeepers help stabilize nations through democratic elections, prevent violence, and disarm ex-combatants. Since 1948, 71 operations have deployed – 57 since 1988 – and over a million peacekeepers have served from 125 countries.

Peacekeeping has evolved in a number of ways over the years. Interestingly, in 1988, at the beginning of the end of the Cold War, there was more cohesion within the Security Council, resulting in more peacekeeping missions. But that has definitely changed recently, and you see that in the way Russia and China have used their veto power. I think this lack of unity is a real concern as we look at peacekeeping moving forward. For example, there has not been a new peacekeeping mission since the mission to the Central African Republic deployed in 2013.

The nature of conflicts has also changed. In places like Mali or the Central African Republic, where peacekeeping faces asymmetric threats, like civil war or extremist groups like Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

With today’s conflicts becoming more complex, how do peacekeepers maintain impartiality?

It is challenging because, in places like South Sudan or Sudan, the government is killing its own people and have been hostile and obstructed the UN in doing its work. The UN is sometimes not given access to certain areas and not allowed to fly their planes to deliver humanitarian aid. When that is happening, it is difficult for the UN to be impartial and also puts the peacekeepers in an awkward situation. In 90% of mission mandates, the primary role of the peacekeepers is to protect the civilians. These conflicts challenge the core principle of peacekeeping, which is the consent of the host country. It is important that peacekeepers are able to do their best in carrying out the primary mandate of protecting civilians.

Peacekeepers help stabilize nations through democratic elections, prevent violence, and disarm ex-combatants.

What are the major policy and strategy dilemmas facing UN peacekeeping today and the future?

What we are really focused on now is the budget. Here at the Better World Campaign, we work to educate Americans and advocate for full funding for UN peacekeeping, but it has been challenging under this administration, which has made drastic cuts. Although Congress continues to be a supporter, it has been harder as we move forward. We have seen that the United States (U.S.) will be in peacekeeping arrears of $500 million by January 2019, which will definitely have an effect on the work that is being done on the ground.

Every three years, the peacekeeping assessment rate is negotiated. This year the U.S. could negotiate its share of the peacekeeping budget down to 25% from 28.4%, which could prevent us from going into additional arrears but would also require other members states and the Security Council to step up and pay more. It is also important to note that a recent Government Accountable Office study confirmed that a UN Peacekeeping mission is eight times cheaper than a U.S. intervention on its own.

As the U.S. begins to retreat, both in engagement and budget, one of the concerns we have is the role of human rights in peacekeeping missions. We have seen that China has tried to cut human rights positions in missions in South Sudan and they continue to cut in other areas as well. This also gives China and Russia an elevated role to push their own agenda which includes and cutting human rights and protection of civilian positions.

The dos Santos Cruz report released in December 2017 recommended that peacekeepers should be ‘strong and not fear to use force when necessary,’ what does this mean? What are the implications? Is the future of peacekeeping peaceful?

Having visited five peacekeeping missions, I have seen what good leadership means and what that looks like. I think one of the critical points in the Cruz report is the change of mindset. Some of the troop-contributing countries believe their role is to stand on the border and monitor a peace agreement. But in areas like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan, and the Central African Republic, robust peacekeeping is needed. This means actively protecting civilians. In Congo, peacekeepers have a mandate to pursue armed groups in eastern Congo, which is more robust than what some of the troop-contributing countries are willing to do. The report is changing the mindset of the leadership to push them to actually carry out their mandate and protect the civilians. Another important thing from the Cruz report is holding countries responsible and accountable when they fail to protect and not do the jobs they are paid to perform. I think that is critical as we move forward.

Peacekeepers are deployed in places where there is not necessarily a peace to keep. The goal of peacekeeping is to create space so a political process can move forward. I think it is really the job of the Security Council and the international community, when peacekeepers are deployed, to push those parties to a political agreement so that peacekeepers can ultimately leave. It is not the job of the peacekeepers to make that political process happen. It is up to the parties, the international community, and Security Council to hold parties accountable to a peace agreement.

A recent government study confirmed that a UN Peacekeeping mission is eight times cheaper than a U.S. intervention on its own.

According to the 2018 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) report, the number of personnel deployed with peace operations worldwide continues to fall while the demand is increasing, how does this fit in the overall UN peacekeeping reform agenda?

Secretary-General António Guterres believes that when UN peacekeepers are deployed, the international community has already failed. We should be doing more on conflict prevention and peacebuilding so when countries come to a resolution, they do not go back into conflict. His reform agenda looks at peace operations more broadly – elevating and strengthening conflict prevention, mediation, and peacebuilding. Peacekeeping is just one of the tools in the set of tools available from the UN. The peace and security architecture is one of the three tracks of reform that the Secretary-General is pursuing.

The UN cannot alone solve these conflicts alone, it needs to elevate those who are already doing the peacebuilding and prevention work on the ground.

Despite their critical role in peacekeeping missions, women represent only a small percentage of UN peacekeepers, why is this so? Are there still barriers that limit/prevent women from participating? How do you deal with peacekeepers involved in sexual exploitation abuse?

In terms of women in peacekeeping missions, we can do better; a lot of troop-contributing countries do not have a large number of women in their ranks. But in Vancouver last year, many countries pledged to support the Canada-led Elsie Initiative, which helps countries train women in peacekeeping. Canada will also offer financial incentives to those countries if they deploy women. Through these financial incentives and training programs, we hope to increase the number of women peacekeepers at a much faster pace.

It is always wrong when peacekeepers are involved in sexual exploitation and abuse. The Secretary-General is taking that very seriously. In the last five years, many reforms have come into play including the ‘name and shame’ list. Three years ago, for the first time, they published every incident that happened and which country was involved, the status of each case, and allegation. Transparency is huge and having that list, which comes out every year and is updated in real time online as cases go to prosecution is a major step. But it is up to the troop-contributing countries to prosecute their own people. The UN does not have that responsibility or authority, which is a challenge; although the UN pushes to have those countries prosecute their own soldiers when these incidents happen.

How can the international community help in preventing the escalation of violence in fragile states?

Within the UN System, it is the role of the Security Council to take up these challenges, but until there is more cohesion within the Security Council, we are not going to see the UN take on difficult situations like in Yemen, Syria, Ukraine, and Burundi. Moreover, keeping these crises in the public’s attention is another thing. The current Sustaining Peace Agenda, a UN and World Bank report, focuses on prevention, and also elevating the role of local NGOs, which is significant for lasting peace. The UN cannot alone solve these conflicts alone, it needs to elevate those who are already doing the peacebuilding and prevention work on the ground.

What most concerns you about the world today? What gives you hope?

I am concerned about the U.S. in the larger global community becoming more isolated. I think the UN is a platform to address global problems, so it is critical that the U.S. continues to be engaged in the global community and with the UN. I am a believer in the UN and the UN peacekeeping. I believe that UN peacekeepers go to places where no one else would go and help some of the most vulnerable in some of the forgotten places in the world.

I am inspired by the work I have seen not just through peacekeeping but through humanitarian agencies. I was in the Central African Republic in May 2017, where five peacekeepers were killed – 4 Cambodians and 1 Moroccan. I was at their memorial service. It struck me that, these soldiers sacrificed their lives in a place they have no family, no loyalty, no national interest, but in the hope for global peace. It is incredibly inspiring. That is what keeps me going. Former Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld said that “the UN was not created to bring us to heaven but in order to save us from hell.” I think UN Peacekeepers do that every day.

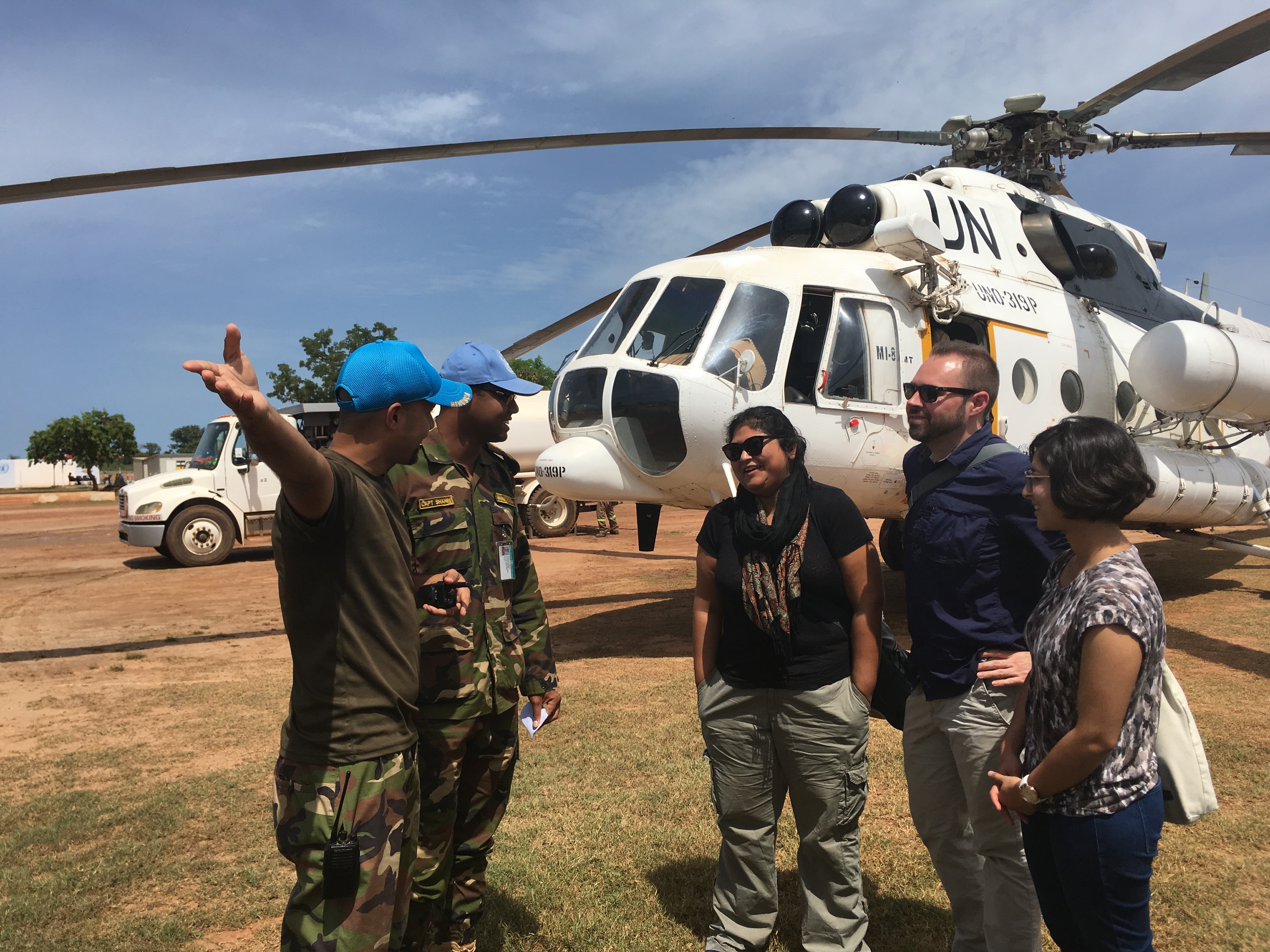

As Peacekeeping Policy Director at the Better World Campaign, Chandrima Das spearheads thought leadership and authors policy papers and field reports on UN Peacekeeping. Ms. Das leads Congressional Delegations to the field to see firsthand the work of UN Peacekeepers. She also served as a special advisor for the UN High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing, providing an American perspective to the panel and her expertise on conflict resolution.

Previously, Ms. Das worked at the United States Institute of Peace as a consultant and research assistant writing training curricula on negotiation, mediation, and conflict resolution. Her training curricula were used to train local government officials in Iraq and Sudan. She has also worked for CHF International in South Sudan on basic services programs and combating gender-based violence. During her graduate study at George Mason University, Ms. Das was a research assistant for the Terrorism, Transnational Crime & Corruption Center, looking at human and arms trafficking routes.

Ms. Das holds a master’s degree in Peace Operations. She received her bachelor’s in Political Science from Syracuse University. She is an International Career Advancement Program Fellow and serves on its board, which works to elevate under-representative groups in international relations and U.S. foreign policy. She is also a Council on Foreign Relations Term Member.

Got something to say?