Impact:Peace is Reducing Violence Through High Impact Peacebuilding

Impact:Peace is a new initiative based out of the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice aimed at leveraging evidence-based approaches to reducing global violence levels. Impact:Peace has a commitment to, “Build a dynamic, agile evidence infrastructure to accelerate and amplify the most promising change processes in the peacebuilding field, whenever and wherever they happen.” Rachel Locke is the Director of Impact:Peace. She recently spoke to VantagePoints about the Impact:Peace mission toward reducing violence across the world, expanding the peacebuilding knowledge base, and realizing Sustainable Development Goal 16.

Impact:Peace is a new initiative aimed at reducing global violence and supporting greater peace. What are some areas you are focusing on as you advance Impact:Peace? How will Impact:Peace innovate on how violent trends are viewed, treated, and then ultimately solved?

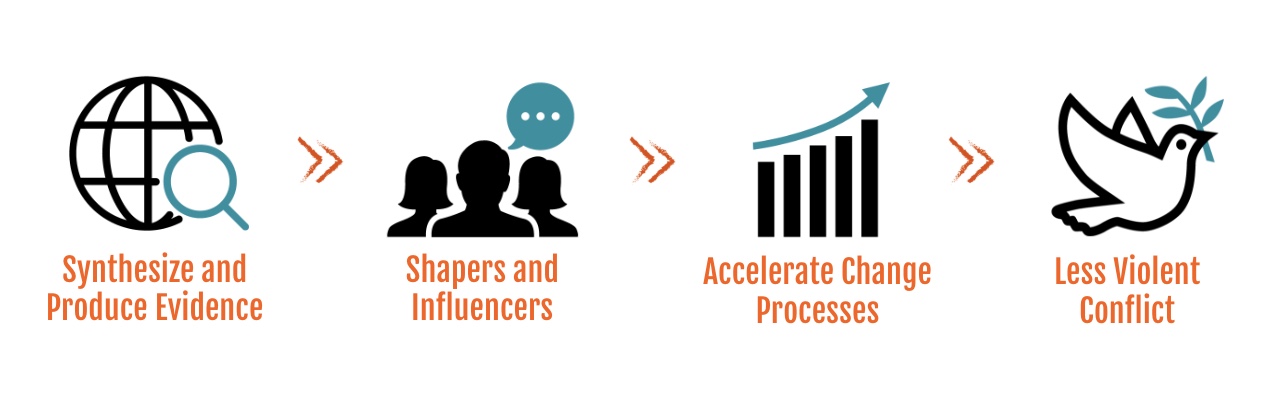

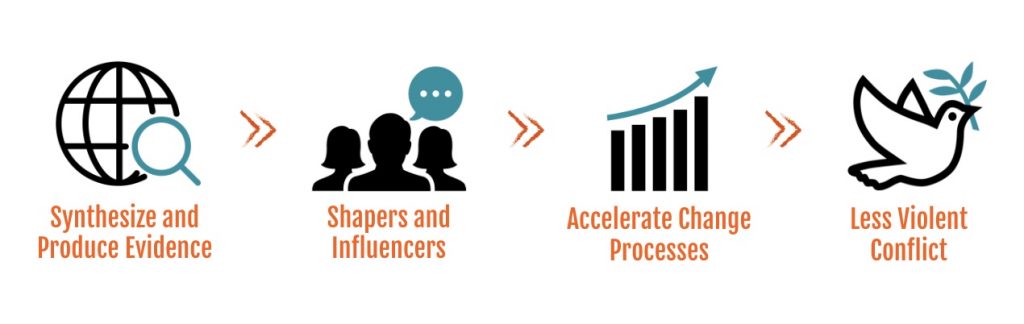

What we’re focused on primarily is what we call ‘high potential change processes.’ Issue areas that have a lot of energy around them, that we see as culminating in a significant positive change in peacebuilding, violence prevention, conflict mitigation, and impact on the ground. While we need to be continuously investing in more and better evidence, our existing research, evidence, and knowledge is quite robust. But just having that knowledge isn’t enough. We are working to connect knowledge and evidence directly to the advocates, shapes and influencers who are driving change processes. In so doing we hope to accelerate those processes, making them, ultimately, more effective.

What we’re focused on primarily is what we call ‘high potential change processes.’ Issue areas that have a lot of energy around them, that we see as culminating in a significant positive change in peacebuilding, violence prevention, conflict mitigation, and impact on the ground. While we need to be continuously investing in more and better evidence, our existing research, evidence, and knowledge is quite robust. But just having that knowledge isn’t enough. We are working to connect knowledge and evidence directly to the advocates, shapes and influencers who are driving change processes. In so doing we hope to accelerate those processes, making them, ultimately, more effective.

One key message is that violence is preventable. We have solid evidence that shows that we can prevent violence before it happens—that we can reduce it once it’s broken out. We can change the trajectory of violence, and this is true across various different forms of violence. This is true in what we call the group or gang violence space. This is true in the conflict violence space. This is true when it comes to violence against women and children. There’s just so much knowledge that exists with regard to what drives violence and therefore the key points of entry to intervene.

Changing the way that violence is understood has to do with changing a fundamental idea that many people in the world have, which is that violence is a fundamental aspect of the human condition. We would disagree with that. Conflict may be part of the human condition, differences of opinion may be part of the human condition. In fact, the space where people disagree is often the space where creativity flourishes. However, we do not believe the violence associated with conflict and dispute is inevitable. Nor should it be considered as such.

We have seen the effectiveness of interventions in reducing and reversing trends in violence. A core innovation is just trying to change that narrative. The vast majority of resources that are put into responding to conflict and violence is exactly that, it’s put into responses. It’s not it put into prevention. We’re really trying to shift that and put much more emphasis on the prevention aspect.

Sustainable Development Goal 16 focuses on “Peace, justice, and strong institutions,” which is a particularly challenging goal. Why has it not received the same attention as the other Sustainable Development Goals?

That is a messy topic unto itself, there are a lot of different opinions. Goal 16 was the most challenging to incorporate into the SDG Agenda and negotiations on its inclusion went down to the wire. Much of the pushback had to do with the fact that Goal 16 is fundamentally political in nature, and there was fear that including components of peace and justice was a means through which to securitize a development agenda. Concurrently there was an appreciation that development without peace is no development at all.

I also think one of the challenges has to do with what I said in response to the first question, which is that we don’t have the consistency of messaging on the effectiveness of strategies that are out there already. Large philanthropists, large donors, tend to feel much more secure in knowing that dollars are spent on health investments, or malaria treatment, or providing textbooks for schools. There is a much easier input-output relationship or at least simplified messages that generate attention and resources even if the challenges are not so simple (i.e. more textbooks don’t automatically mean better educated children or greater education equity).

Those of us working on conflict and violence have not perfected these clear and consistent messages. In part, that’s because this is a very messy space. It is very political, and it’s not easily quantified. We have really big data gaps, particularly in some parts of the world. People pay for what they can measure. But we are working on it; significant efforts are going into improving data and this will, I think increase awareness and attention to the scale and scope of violence in the world today.

The Sustainable Development Agenda and Goal 16 in particular is helping push this conversation, animating more investment in measurement, in how we communicate. It’s a huge opportunity.

In your opinion, what will it take to realize SDG 16?

First and foremost it’s going to take knowing that we can make progress. It’s also going to take the political will to really understand some of the major gaps, and how to reframe and rethink very structural issues within society. In the justice realm for example, there’s been work demonstrating massive justice gaps. The number of people who don’t have access to justice—the fundamental provision of justice within communities—is the majority of the world’s population. That’s a call to action. Not just justice for the few, justice for an elite few, but really reframing what we should be thinking about when we think about access to justice.

Countries and cities and jurisdictions have to decide that they are making a commitment. That is true whether we’re talking about justice, or whether we’re talking about preventing conflict or violence, or whether we’re talking about creating institutions that are more inclusive and less exclusive. There is a political challenge here. That’s part of what is animating Peace in Our Cities (see next section) – generating political leadership.

Another thing we need is resources. We need much more significant investment. Violence and conflict prevention receives a paltry percentage of overall foreign assistance. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, only 2% of total Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) to fragile contexts goes into conflict prevention. What does this mean? In those countries at highest risk of violence a near negligible amount of ODA is being spent on reinforcing aspects of society that can prevent conflict and reinforce resilience. This can be compared to doctors performing costly emergency surgery rather than investing in a strong primary healthcare system that keeps people and communities healthy and productive.

There is somehow this idea that we can invest extremely small sums of money and see massive reversals in conflict and violence trends. People don’t expect that in the health sector. I don’t know why people should expect that when it comes to building peace. There needs to be a seriousness of purpose, and seriousness about investing in saving lives and supporting peaceful societies.

Impact:Peace, alongside +Peace and the Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies at NYU, is co-facilitating the Peace in Our Cities campaign which launched on the International Day of Peace this year. Peace in Our Cities is focused on reducing violence by 50 percent by 2030 in cities across the world. What can we learn from focusing on urban violence that might not be readily apparent to stakeholders such as mayors and other jurisdictional authorities?

We have lots of examples of cities that have massively reduced their violence levels. I’m thinking about Medellin. I’m thinking about Ciudad Juarez. Those were cities that were labeled as having the highest homicide rates in the world at some point. We have Oakland, California which achieved a 50 percent reduction. We have examples from all over the world, of cities that have effectively done the work of reducing and preventing urban violence.

Another thing we can learn from focusing on urban violence is that singular approaches are never sufficient. Much of the evidence from the urban violence space reinforces that it’s about a balance of interventions that includes the justice sector, the right kind of law enforcement, balanced with real action at the community level and prioritizing the voice of those most affected, balanced with investments to improve relationships between people and their government.

There’s

Often when there’s an uptick in violence you hear politicians, and frankly constituents, calling for heavy-handed law enforcement response. You see that in a number of places, including Mano Duro approaches in Central America. You also see that in the US, and in many other places where people tend to think the only way to respond to violence is through “tough on crime” police or militarized response. The evidence says these approaches are not most effective; but feelings are not always based on facts.

But I would add that Mayors and other municipal actors are typically very aware of these dynamics as they are at the forefront of many of today’s presentations of violence. Many mayors are motivated to take steps to make their cities safe for all – this is what the mayors who have joined Peace in Our Cities are demonstrating. Very often it’s more a matter of spreading knowledge of positive practice, generating sufficient resources and investing them wisely, and building coalitions of partners than it is a matter of a lack of urgency or imperative.

There’s a lot of conflicting information regarding the current levels of violence in the world. How will Impact:Peace develop a strategy that will support evidence-based outcomes in managing violence?

People think about lethality and they think about conflict zones. They don’t think about countries and places with very high levels of violence that exist outside of conflict. For example, many people don’t realize that Brazil and Mexico constitute two of the most lethal countries in the world. If we’re going to be talking about evidence-based solutions to address violence, we have to start with knowing—where is the violence, and what’s the kind of violence that we’re talking about?

People think about lethality and they think about conflict zones. They don’t think about countries and places with very high levels of violence that exist outside of conflict. For example, many people don’t realize that Brazil and Mexico constitute two of the most lethal countries in the world. If we’re going to be talking about evidence-based solutions to address violence, we have to start with knowing—where is the violence, and what’s the kind of violence that we’re talking about?

One of the strategies is really just pushing that knowledge out, not just to policymakers and experts, which is certainly part of what we’ve been doing. It’s also getting people really animated by the fact that we have many of the tools to effectively address violence, whether that be urban or community violence, conflict violence, violence against women or children. We don’t have magic and nothing works all the time, but we have a huge resource base of knowledge; we need to act on it.

I spend a lot of my time sort of connecting the dots, talking to various policymaker, experts, academics, practitioners, and asking, “Have you seen the latest research on this?” Very often, frankly, they haven’t. That’s not their fault, that was true of me when I was a policy maker. There is a lot of material being produced and knowledge being generated – that’s a good thing! Getting it to the right people, in the right way at the right time, that has to matter more. Doing the work of curating and deploying knowledge – that’s our goal.

To do that is both an art and a science. Understanding narratives that people best respond to, understanding the right timing to deploy information, taking advantage of media cycles, taking advantage of moments on the calendar, partnering with the right people who serve as influencers or multipliers. That’s all part of our strategy.

What will it take for a global shift from response to prevention in solving the issue of violence?

Proving that we can prevent violence. That’s a big part of it. I also think really listening to the voices of youth and women is of particular importance and urgency. There’s been a lot of work done under a framing of empowerment. Empowering women, empowering youth. This is important, but there’s been far less investment in ensuring that their voices are heard. That’s a different thing. There needs to be far more accountability placed on those unwilling – historically and currently – to listen.

There’s a lot of evidence about how different forms of violence are increasingly overlapping. You have contexts where you have criminal groups operating. You have the vestiges of political conflict. You have high levels of interpersonal violence and violence within the home. We need to pull from effective programming in the conflict space, the interpersonal violence space, the group violence space. But also we need to see how specific individuals, communities and governing systems are often impacted by more than one type of violence concurrently and, indeed, how they influence one another.

There’s a lot of work that’s being done to figure out what to do in those environments. At the same time, there’s also a consistent finding, which shows that the societies that are more gender-equal tend to have lower levels of violence across the board. Increasing equality across the genders could be one of those key areas of investments.

I also believe there needs to be greater appreciation for the evidence that demonstrates that militarized responses to violence is not typically most effective, nor cost-efficient nor life-saving. Militarized approaches also have substantial knock-on effects that undermine more resilient and peaceful societies in the long-term. There continues to be an overly heavy reliance on militarized responses. A shift in that thinking and that narrative is also required.

Finally, it’s past time that we start acknowledging the need for substantial resource investments; we can do something here, but we can’t do it with peanuts. Only one percent of global philanthropic goes towards peace, which begs the question: Why is there no Gates Foundation for building peace?

Sustainably reducing violence and building peace requires a careful balance of necessary elements. Are there examples of successful peace-building initiatives that have inspired your approach to Impact:Peace?

I think it’s often important to go back to fundamentals, which is a basic imperative to work with key people and more people. Core peace-building work of breaking down barriers, increasing trust, reinforcing common humanity, particularly when there’s been historic tensions or animosity, this is essential.

Also essential is focusing on key people. That includes key policymakers, politicians, leaders who are making decisions about where to make financial investments, who are mobilizing others towards violence or towards non-violence. This also includes leaders making decisions about weapons. After the Christchurch attack in New Zealand, decisions were made within a day to implement sensible gun regulations. We saw this in Australia years ago as well. Focusing on those vested with the power to make changes is also essential.

This requires a horizontal and vertical approach. Where you see those two things come together, is where you see the reduction in violence in the near term that’s sustained in the long term.

It’s important to acknowledge that very often expert communities operate at cross purposes, with some more focused on ‘stabilization’ or bringing violence down in the very near term while others are more focused on long term processes and addressing ‘root causes.’ I think it’s incumbent upon us to bring these communities together. We need to bring violence down today and we need to keep it down tomorrow. We need to think about what is needed to help us do both these things at the same time.

Stabilization and long-term prevention – when done right – can reinforce one another by increasing faith within particular communities that the government is taking the violence seriously while respecting human rights and community priorities. When done wrong it can reinforce negative relationships, making prevention harder in the long term. Bringing these communities together will not happen overnight, but there are signals that there is increasing communication, which we just need to deepen.

What concerns you most about the world today? What brings you hope?

The things that concern me most about the world include an increasing isolationism. We see it at the individual level and at the national level. I think that there’s sort of an irony in the fact that the world has become much more and more globalized, yet a reaction to that globalization, coupled with technology and social media, is that people are retreating and countries are retreating. We see this with the significant rise in authoritarian regimes around the world. I think we see this in very high levels of suicide around the world—a sense of isolation. We see this in patterns of recruitment of people joining violent movements. Whether we’re talking about extremist groups, or gangs, or right-wing militias, or otherwise, members often cite a sense of marginalization and isolation as part of their motivation.

This extends to a retreat from our multilateral systems. These systems – the UN, the EU, NATO – may have prevented a World War III. They’ve helped to prevent escalations of violence in many parts of the world. They’re essential to managing how states work together. Retreating from these systems gives me a lot of concern.

What brings me hope? What brings me hope is that in the face of all of the tragedy and awful stuff that happens, our trajectory of human history, from the perspective of violence—in generational terms, I’m not talking year-to-year—continues to decrease. We have gotten less violent, safer, healthier (recent data on U.S. decline in life expectancy not-withstanding). I think that’s something to take really seriously. Humanity is going to have tragedies—and the fact is that we recover, we move forward, we improve, we extend those improvements to other aspects of our lives, to new areas, new locations. I think that that gives me hope.

Add to that the amazing acts of kindness that people extend to other people every day, these incredible acts of bravery—people standing up to repressive governments, people bearing witness, people sharing their pain in order to make their communities and their world safer. That has got to give you hope.

Rachel Locke joined the Kroc IPJ as Director of Impact:Peace in July 2019. Rachel has extensive experience delivering evidence-based violence prevention solutions to some of the most difficult international contexts while simultaneously advancing policy for peace. Prior to joining IPJ, Rachel was Head of Research for violence prevention with the Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies at New York University’s Center on International Cooperation. In this capacity, Rachel led coalition building and evidence curation with the UN, bilateral governments, the African Union, civil society and others to explore the challenge of delivering the 2030 Agenda targets for peaceful societies (SDG 16.1).

Earlier in her career, Rachel served as Senior Policy Advisor with the US Agency for International Development where she developed and represented agency-wide policy on issues concerning conflict, violence and fragility. She also led USAID research and policy on crime, conflict, and fragility and worked extensively on program design, implementational and evaluation primarily in Africa. After leaving USAID, Rachel launched a new area of work for the National Network for Safe Communities at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, bridging effective violence reduction approaches from the U.S. to municipalities globally. This work involved direct collaboration with law enforcement, national and city-level government and civil society actors. Among other initiatives, Rachel launched a three-year effort across two states and five municipalities in Mexico at a time of exceptionally high violence.

Rachel’s experience bridges the humanitarian, development, peacebuilding and urban violence realms. She holds a Master’s in International Affairs from Columbia University, Graduate School of International and Public Affairs. She has also published a variety of articles and other works focusing on violence prevention, humanitarian aid, conflict and transnational organized crime.

Got something to say?