DROP-OUT OR PUSH-OUT? MICRONESIAN STUDENTS IN HONOLULU

By Sheila M. W. Matsuda

As one public school teacher in Honolulu explained to me, “A drop-out is a person who has been guided toward alternative education because he or she won’t have the right credits to not drop out. The number of credits needed to graduate is not attainable without good English or a good transcript.” In a separate discussion, a mother of a Micronesian student told me that Micronesian students “are told they cannot graduate because they don’t have enough credits so they get pushed out of school into youth programs.”

These testimonies, reflecting two sides of the same urgent issue, are part of an extensive study I conducted over the past year in which I gathered opinions on the status of Micronesian students in Honolulu’s public schools. The study was set amid a growing sense of urgency in Honolulu. Citizens of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) have protected status with the United States (U.S.) under the Compact of Free Association (COFA). In exchange for the U.S. to use Micronesian land, air, and seas for U.S. military purposes, the COFA permits Micronesian citizens to freely migrate to the U.S. without a visa and entitles COFA migrants to public services.

An estimated 107,000 COFA migrants currently reside in the state of Hawaii, 75,000 of which are from the FSM. As the number of COFA migrants to Honolulu has increased, so also have the intensity of public discourses around education, health care, and affordable housing. Micronesians come to Honolulu with the hope of a better life for their children and for themselves. They dream of a good education, adequate health care, and the possibility of finding a job. Upon arrival in Honolulu, however, Micronesians face discrimination, lack of affordable housing, a politically charged healthcare environment, and a contentious—rather than secure—place in the public education system.

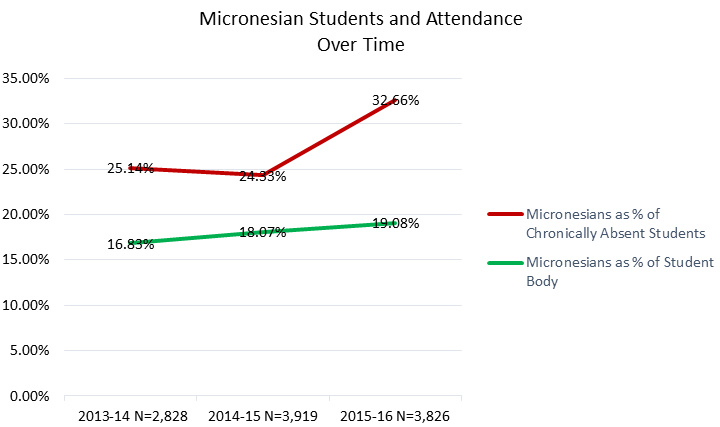

It is widely believed that Micronesian students in Honolulu are not doing well in school. To the schools, it means that students do not attend school and do not progress through the system to eventually graduate. Schools talk about absenteeism and relate that to low achievement. Indeed, Micronesians make up the largest percentage of students designated as chronically absent, a rate of absenteeism has been increasing (Figure 1). Schools blame absenteeism and drop-out rates on lack of parental involvement which, to them, indicates that Micronesians do not value education.

Meanwhile, parents of Micronesian students contend that their children are not able to reach their full potential in public schools. Parents say that their children are labeled as incompetent and trapped by the English Language Learner (ELL) designation. Most Micronesians in Honolulu are from the state of Chuuk, identify as culturally Chuukese, and speak Chuukese languages. Many parents blame the schools for cultural and linguistic discrimination that prevents their children from benefiting fully from Honolulu’s schools. Parents believe these and other factors cause Micronesian students to be “pushed out” from the public school system.

Figure 1. Micronesians as percent of chronically absent students

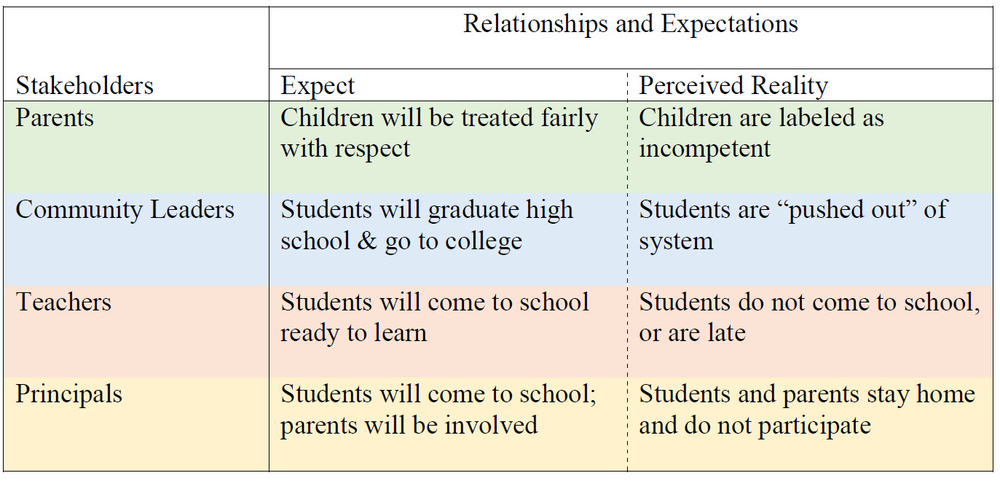

Stakeholders who have an interest in improving education for Micronesian students recognize that the current approach to educating these students is not achieving the desired results. All agree that they want Micronesian students to be successful in school—but there are gaps in perceptions of the challenges (Table 1). How can stakeholders move beyond their narrow perspectives and work cooperatively for effective change that will benefit the Micronesian student population?

Table 1: Comparison of expectations and the perceived reality

My research into this issue sought to give voice to teachers and principals, as well parents and community leaders, regarding expectations and the issues hindering Micronesian student engagement. In particular, the study aimed to capture the perceptions of teachers and principals directly involved in the public education of Micronesian students. To that end, between June 2015 and February 2016, I interviewed 57 community leaders, service providers, government representatives, teachers, principals, and parents. Participants shared opinions of feasible solutions to problems related to language and intercultural understanding. Some of the solutions suggested may contribute to viable long-term solutions to the problems of chronic absenteeism and high drop-out rates for this population. I also analyzed student demographic and attendance data from 4 target schools with an average of 30% Micronesian student population to probe relationships between ethnicity and attendance patterns.

- Credits required for graduation can only be earned from regular classes. Students with English Language Learner (ELL) designation cannot take regular classes. Proficiency in academic English is necessary to pass out of ELL. Scholars agree that it takes five to seven years to acquire the academic English skills needed to perform at grade level. According to principals and ELL coordinators, students in Hawaii must exit high school when they are 18 years old whether they graduate or not. Students that arrive from Micronesia with little formal schooling and with little English language experience are required to take ELL classes until they prove academic English proficiency. At the high school level, they are not allowed to take regular classes that count toward graduation until they pass out of ELL. Because it takes several years to learn the academic English necessary to pass out of ELL, they do not have time to earn enough credits to graduate from high school before the high school age limit. This policy effectively pushes older students to drop out because there is insufficient time to complete graduation requirements. One mother complained, “In my family alone, two kids ‘dropped out’. They were encouraged to drop out! They were told that they can’t make it in the school.”

- Age-based grade assignment without an introductory primer course forces newly arrived students to learn everyday English, academic English, and subject content at the same time. Upon arrival in Hawaii, students are assigned to a grade based on their age, regardless of English ability and without a crash course in basic, fundamental English. Schooling is inclusive through grade eight. That means that a nine-year-old child who arrives in Honolulu from Chuuk will begin immediately as a 4th-grader in a regular classroom. The classroom teacher is responsible for teaching the child the 4th grade curriculum even though the child does not know any English. A student coming into 8th grade must learn the ongoing subject content and all the knowledge that led up to 8th grade while also learning English. At the high school level, the policy is different. All students 14 years or older without transcripts are assigned to the 9th grade, regardless of age. As explained above, if the student’s English is not adequate, the student will not take regular credit-earning classes. Regardless of their progress in English, they are required to take the same high-stake tests as all students after one year in Hawaii. Teachers expressed dismay that the “same test (is) given to these ELL kids as native speakers.”

- School personnel, including teachers, principals, and staff, are not familiar with Micronesian geography, languages, cultures, values, or customs. Misunderstandings, miscommunication, and non-aligned assumptions and expectations stem from lack of information. One teacher who attended a professional development training about Micronesian culture said, “If you take the time to learn about Micronesia, it makes teaching easier; you can understand who they are instead of making guesses and inferences, and sometimes negative judgments about their culture—you can be more understanding.”

- Families arrive in Hawaii without an orientation to the language, customs, and laws of Hawaii. Parents may not speak English and may not know or understand American etiquette or societal rules of engagement. They are unfamiliar with American school culture and the expectations they are supposed to live up to. “New parents don’t know the school parent culture. I never went to PTA because I never knew about it,” commented one parent. Others added, “We didn’t know about volunteering in the classroom so we didn’t. We didn’t know about taking treats for birthdays so we didn’t. Someone could have told us!”

- Communication between schools and parents as well as among schools is needed. Schools need to communicate their expectations to parents, parents need to communicate their expectations to schools, and schools need to communicate curricular expectations to feeder schools. Parents complained, “Except for school supplies, we didn’t know what the school or teacher expected of us.” “The school didn’t call when she had difficulties with school work, homework, or tardiness. They only told us at the end of the year.” The schools do not understand the reasons behind the parents’ hands-off approach to education. Schools need to know the parent perspective: “When we send our kids to you to school them, you become the parent of that child and you are expected to take care of them.” Among schools, communication regarding curricular expectations is lacking. Teachers and principals alike commented, “The curriculum at feeder schools is different from our curriculum.” “They don’t articulate with us. We need to coordinate. What are we doing here and what are you doing there?”

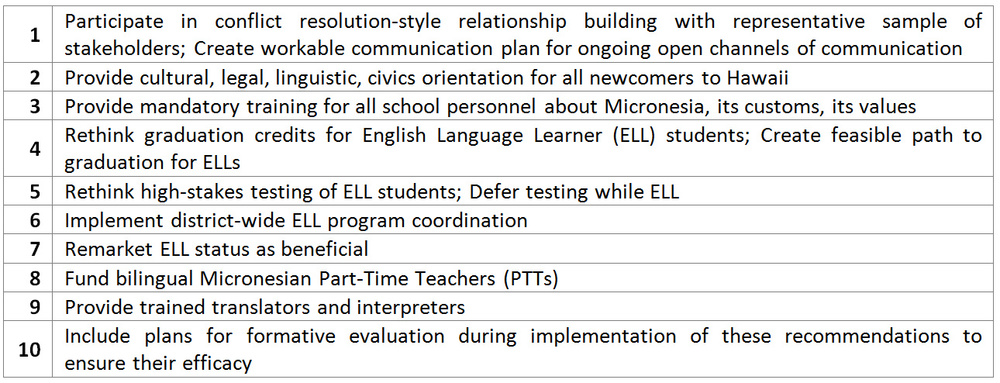

Overall, my research exposed widespread finger-pointing; the challenges of educating Micronesian students are blamed on others. To encourage positive movement toward cooperative problem-solving, I suggest that stakeholders first engage in conflict resolution-style relationship building. Further recommendations to begin to address student achievement include many that teachers themselves suggested in interviews (Table 2).

Table 2. Recommendations

My next step will be to circulate these findings and recommendations to policymakers, community leaders, community organizations, and other relevant stakeholders in Honolulu—to help raise awareness among stakeholders about the expectations each group has of others and the perceptions of the issues that affect Micronesian students. Future steps include the possibility of establishing a new collaborative platform for all community members and stakeholders to communicate, work together effectively, and take concrete action to enhance Micronesian students’ success in the education system. In the words of one community leader, “I think that the kids are very bright, but they’re not given a chance to really fly.” When stakeholders work together to improve the way Micronesian students experience education in Honolulu, Micronesian students will shine.

Sheila Matsuda is a graduate of Teachers College, Columbia University and an expert in intercultural communication and Japanese language and culture. You may reach her at sheila.walters.matsuda@gmail.com to request the full policy briefing.

Print version [PDF]

Got something to say?